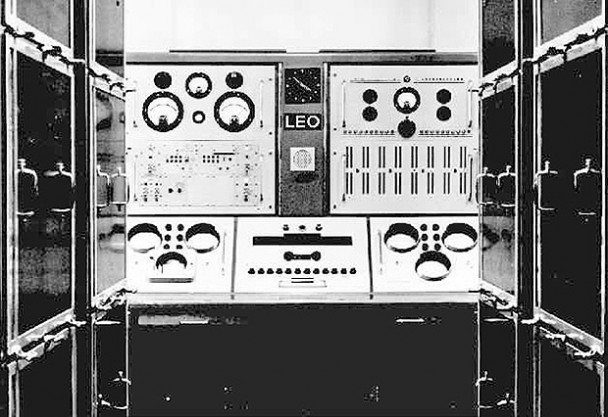

In the buzz around Big Data, it’s worth remembering that analytics is as old as business computing itself. In 1953, LEO (short for Lyons Electronic Office) was the first computer in the world used to manage a business – and for the first ever analytics applications.

J. Lyons & Co. wasn’t a computer company: with over 30,000 employees, it was famous for making fine tea and cakes (its bakeries manufactured 36 miles of swiss roll every day) and serving over 150 million meals a year in Lyons teashops across the UK.

Previous “electronic brains” such as ENIAC were built by the US Army and concentrated on calculating missile trajectories. Lyons’ problem was a little different. According to the book A Computer Called LEO by Georgina Ferry, Lyons struggled with an issue that will still be familiar to anybody running retail businesses today:

“Almost every item sold in the teashops was perishable. If it were not sold within a day of delivery it might be wasted; if too few of any item were ordered, valuable sales would be lost.”

Lyons was “excited by the possibility that LEO could produce the kinds of figures on the performance of each teashop and each product sold there that could enable the managers to make well-informed decisions.”

The computer was designed and built by Lyon’s own engineers to grapple with predictive analysis: the task of “restocking each teashop every day with no more and no less than it needed to keep its customers supplied with bread rolls, boiled beef, and ice cream.”

The very first job to run on the new computer in 1951 was “bakery valuations” and by 1954, the system was fully operational, used for standard reports:

“LEO kept running totals of different product lines and printed them out at regular intervals, so that managers could see at a glance what was popular and what was not. It converted orders for portions of composite cooked dishes, such as boiled beef, carrots, and dumplings into quantities of the separate items so that they could be produced and dispatched separately. It recorded the sales value of the goods delivered to each shop, so that they could be compared with the takings at the end of each month.”

More sophisticated “management by exception” reports:

“For a range of different products, LEO could print out the ten best and ten worst performing shops. Managers would then be in a position to investigate the factors that were affecting performance and make adjustments accordingly. The could also compare advance estimates of goods required with the daily amended orders to see if manageresses were consistently over- or underestimating their future needs.”

And product quality reporting:

“LEO was even used to ensure that Lyons continued to produce the perfect blends of tea on which so much of the company’s reputation rested.”

Fascinatingly, some of the biggest cultural issues that plague analytics success today were also present in the dawn of business computing. First, some of the business problems were being caused by the company’s own choice of performance indicators:

“The worst crime a manageress could commit was to order more than she needed. At the end of the day if you had four rolls left that was four black marks, so manageresses looked at what they might sell and took a bit off and underordered.”

The inevitable result was that shops over had empty shelves in the afternoon, resulting in untapped revenue potential and customer dissatisfaction.

The second issue was getting top managers to adapt their management style to the new possibilities:

“The teashops division was possibly the most conservative part of an essentially conservative organization. The most advanced data processing system in the world was in the hands of a management whose style had changed little since the nineteenth century… The LEO team had designed the system that they would have like to have had if they had been running the teashops, not one that the managers themselves had asked for. The managers still liked having their printouts of everything that was happening everywhere.”

So despite all the hype about “new” analytics and big data, it’s clear that the underlying business goals have remained remained remarkably similar over the decades — “well-informed decisions” is still the stated goal of most analytics projects.

What is different, of course, is that today’s systems are infinitely more sophisticated and powerful than LEO’s valves and mercury tubes.

But the next time you hear a presenter talk about how an analytics product is revolutionary because it helps businesses “look into the future, not just back at the past,” I invite you to think back to the hundreds of miles of swiss roll that wasn’t wasted because of LEO’s pioneering calculations more than half a century ago!

Comments

3 responses to “The First Ever Business Intelligence Project”

The pressures on organizations are at a point where analytics has evolved from a business initiative to a business imperative.”Really very useful information is shared. Thanks so much for sharing it.

[…] By Timo Elliott, from: https://timoelliott.com/blog/2014/05/in-the-beginning-was-analytics.html […]

[…] Business analytics blog: “The first ever business intelligence project” In this blog, a former colleague of mine, Timo Elliott, writes about the first BI system, which dates back to 1953. This is an interesting look at the many business problems that early system was built to solve, since most of them are the same issues modern BI and visualization tools are trying to address today. […]