It’s the start of the year, and organizations around the world are holding kickoff meetings in order to explain new incentive systems to their employees.

These plans are typically the result of many months of painful negotiations, as corporate stakeholders debate the perfect set of incentives to support the organization’s strategy.

But every system of incentives inevitably opens up the possibility of dysfunctional behavior. Not necessarily because employees are corrupt, but because they feel pressured to “meet the numbers” – and because daring to question the value of corporate KPIs is actively discouraged.

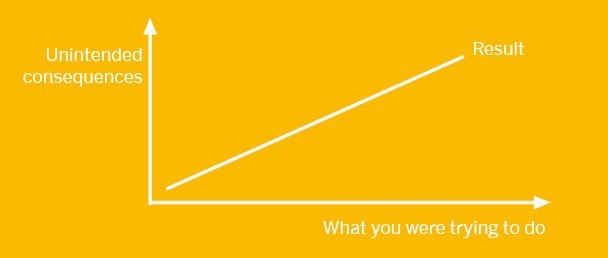

Dysfunctional behavior is just as predictable as the desired effects.

Dysfunctional behavior is by no means a new area of business management theory, and there are dozens of books available on the topic (e.g. Misleading Indicators).

Here’s a couple of examples that jump to mind:

- An emergency department of a hospital defined a KPI on the percentage of patients that were seen in less than an hour. It sounds like a reasonable number to keep track of – but when faced with the choice between a patient that arrived 62 minutes ago and a patient that arrived four minutes later, doctors would chose to see the later patient. Even though this meant taking patients in the wrong order, the second patient could be “saved” from a KPI point of view, whereas seeing the first patient – who had already waited more than the 1hr limit — would make no difference to the numbers.

- A software company wanted to increase sales through reseller partners. To encourage the direct and indirect teams to work with each other, sales management introduced new incentives: the direct sales team would get paid full commission on any deal involving their customers, even if it went through a partner. The unintended result was that some sales people would negotiate a deal directly with a customer, and then at the last minute go to a partner and offer to let them sign the deal, in return for a share of the partner rep’s commission. The KPI for indirect sales was spectacularly overachieved. The problem was, of course, that average deal profitability fell through the floor. Some decrease had been expected, but the full extent of the problem wasn’t appreciated until most of the year had gone by.

In both cases, the bad behavior was perfectly predictable in advance, and would have been very easy to track – yet came as a complete surprise when it was discovered.

Sadly, the problem is commonplace: most organizations don’t realize that dysfunctional behavior is happening until the bad effects become obvious.

The underlying problem: human nature

Why do managers who spend so much time defining key performance indicators and targets not spend the additional time necessary to make sure they’re working as planned?

For an answer, I turned to an expert. Frank Buytendijk is a Gartner Analyst and the author of a series of books that explore the intersection between human behavior and business performance, including Performance Leadership, Dealing With Dilemmas, and Socrates Reloaded – The Case For Ethics in Business and Technology.

Frank’s (slightly edited) reply over twitter:

“Many see business as amoral, and it simply doesn’t come up. They are honestly surprised with the sh*t hits the fan. It’s a difficult topic, so people avoid it.”

In other words, it’s a blind spot in human nature – which is why the problem is so prevalent and durable. However, there’s at least one easy thing organizations can do to help alleviate the problem.

Dysfunctional behavior analytics

If you’ve just unveiled your new incentive plan, you have one more thing you have to do: work out what bad behaviors could result and put in place analytics designed to alert your managers whenever that bad behavior is detected. Analytics won’t stop bad behavior from happening, but will enable you to intercede before too much damage has been done.

For more on how not to do planning, I recommend a great Harvard Business Review article on “The Big Lie of Strategic Planning”